Ossetian or Ossetic is the most widely spoken Northeastern Iranian language, spoken by more than half a million people mainly in Russia’s “Republic of North Ossetia-Alania” and the disputed territory referred to as South Ossetia where a struggle for independence from Georgia has been under way since 1991. Ossetian is an official language in both territories, and is written using the Cyrillic alphabet.

In spite of its geographical location, Ossetian is typologically a Northeastern Iranian language along with Yaghnobi. Ossetian speaking regions are geographically isolated from the rest of the Iranian family, and Ossetian has therefore been beyond the sphere of influence of other Iranian languages, including Persian. Instead, it has been under the influence of the genetically diverse languages of the Caucasus (and in recent centuries, Russian), which is reflected in many aspects of its grammar and vocabulary. Bilingualism between Ossetian and the Caucasian and Turkic languages of the region is common, and in South Ossetia bilingualism between Ossetian and Georgian is the norm. In addition to these, the presence of Russian is strong in both regions.

In Ossetian, using the name of the dialects instead of an umbrella term is more common. The two major dialects of the language are Iron ævzag (Ирон æвзаг, lit. "Iron language") and Digoron ævzag (Дигорон æвзаг), with Iron being the dominant one both culturally and demographically. The two dialects have low mutual intelligibility, and diverge from each other considerably in phonology, syntax, and vocabulary. The examples and grammatical notes in this article are based on the Iron dialect.

Ossetian is a descendent of the medieval Alanic language (spoken by the Iranian people known as Alans in late antiquity). It is the only surviving descendant of the ancient Eastern Iranian Scythian languages that are believed to have been in use in vast areas of Eastern Europe and Central Asia in ancient times.

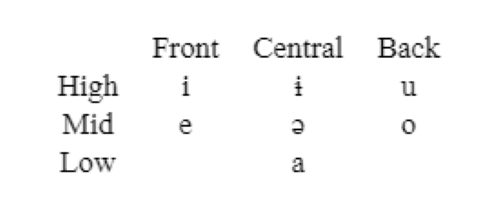

Vowels

Ossetian (the iron dialect) has 7 vowels: two front vowels /i e/, two back vowels /u o/ and three central vowels /ɨ ə a/. Moreover, the vowels /ɛ/ and /ɪ/ appear in borrowed Russian words. A vowel chart is presented below.

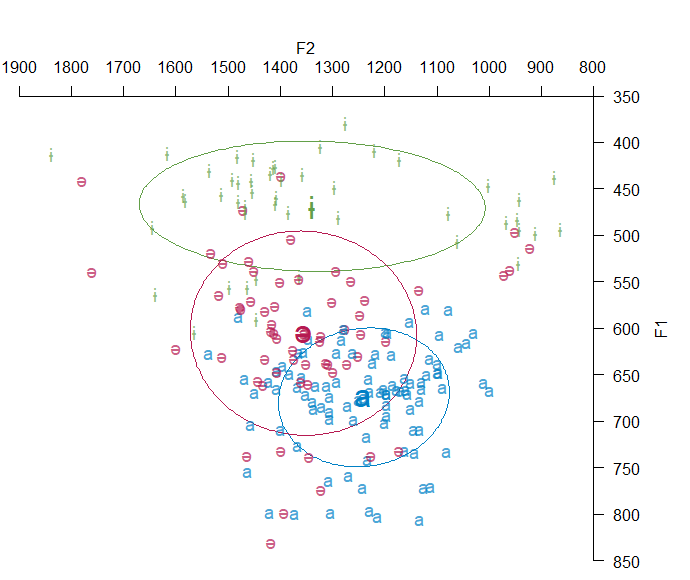

There is some debate among sources on whether /ə/ and /a/ are central vowels. Part of the problems stems from the fact that /ə/ frequently assimilates based on its environment (Hettich 2002). Most sources agree that /a/ is a low unrounded vowel, but it also features varied F2 values (Abaev 1964; Hettich 2002). Using data collected by the NSF grants that support the current project, we created a preliminary bark chart to visualize the phonetic properties of the central vowels (presented below). There are no significant differences in F2 values between the /ɨ ə a/, which supports the conclusion that Iron Ossetian features three central vowels. It is important to note that there is a wide variation in the production of the weak vowels /ɨ ə/.

Scholars often devide the vowels into the strong (/i e u o a/) and weak (/ɨ ə/) groups (e.g. Isaev 1959, Abaev 1964, Hettich 2002). The weak vowels frequently reduce and delete (especially when adjacent to strong vowels) and appear epenthetically to resolve clusters. The strong vs weak distinctions also play a large role in stress assignment (see below). The strong vowels /a/ and /o/ alternate with /ə/ in plural formation, past tense, and in compounds. It is well known that the strong vowels were historically long (Isaev 1959, pp. 32-33) and as acoustic measurements by Dzakhova (2010) show, they are still longer in duration.

The following chart presents some minimal pairs for the vowels:

|

a, ɨ |

mad ‘mother’ |

mɨd ‘honey’ |

|

|

a, ɨ |

maʃt ‘bitter’ |

mɨʃt ‘mouse’ |

|

|

a, e, ɨ |

bal 'cherry' |

bel 'shovel' |

bɨl 'lip' |

|

a, u |

zag ‘full’ |

zug ‘herd of sheep’ |

|

|

a ə |

ʒʁalɨn 'to pick pieces off' |

ʒʁəlɨn 'to have pieces fall off' |

|

|

u, ə |

tuxɨn 'to fold' |

təxɨn 'to fly' |

|

|

i, ə |

ʃin 'thigh' |

ʃən 'wine' |

|

|

ə, ɨ |

ləg ‘husband’ |

lɨg 'cut' |

|

| o, ɨ | bon 'day' | bɨn 'bottom' |

Consonants

The main distinctive property of the Ossetian consonant system among Iranian languages is the presence of ejective stops and affricates, which is thought to be the result of areal influence from the surrounding Caucasian languages. In Ossetian, stops and affricates (excluding the uvular sounds) have a three-way distinction: voiced, voiceless, an ejective. Ejectives are more common in loanwords. According to Thordarson (1989), the functional load of ejectives is insignificant in Ossetian (in contrast with Caucasian languages). This means that simple minimal pairs distinguishing ejectives versus plain voiceless consonants are rare in Ossetian. The Ossetian consonant inventory is shown in the table below.

| bilabial | labiodental | alveolar | postalveolar | palatal | velar | uvular | ejective | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plosive |

p b pʼ |

t d tʼ |

k g kʼ |

q

|

||||

| fricative |

f v

|

s z

|

ʃ ʒ

|

χ ʁ

|

h

|

|||

| affricate |

t͡s d͡z t͡sʼ |

t͡ʃ d͡ʒ t͡ʃʼ |

||||||

| nasal | m | n | ||||||

| trill | r | |||||||

| approximant | w | j | ||||||

| lateral approximant | l |

According to our own data collection as well as work done by Erschler (2018), voiceless stops are aspirated syllable initially and released word finally but are unaspirated in clusters (e.g compare [ʃtəg] 'bone' and [tʰəχɨn] 'to fly'). For velar and uvular consonants, Ossetian makes a distinction between plain and labialized phonemes. Velar and uvular consonants can be labialized when they precede /ɨ/. All consonants can also be palatalized when they precede a front vowel /i/ or /e/. Labialized and palatalized consonants have been omitted from the consonant inventory presented above due to their allophonic distribution. Examples of both are presented below.

Palatalization

|

fʲ |

fʲet:aj |

'saw (2.sg.pst.PERF)' |

|

nʲ , ʃʲ |

nʲeʃʲi |

'melon' |

|

mʲ |

mʲe-ma |

'with me' |

Labialization

|

qʷ |

qʷɨˈmas |

'fabric' |

| χʷ |

xʷɨ |

'pig' |

| kʷ |

kʷɨz |

'dog' |

| gʷ |

gʷɨr |

'torso' |

Gemination

Most consonants can be geminated both at morpheme boundaries and within a morpheme. The orthography in Iron Ossetian marks gemination by doubling the consonants. Compared to singleton voiceless stops, gemination of voiceless stops results in minimally aspired consonants with double length closures. Some examples of words with geminates follow

| /pərːəʃt/ |

flapping |

| /təkːə/ | now |

|

/wərɨkː/ |

lamb |

| /bətːɨn/ | to tie |

| /dətːɨn/ | to give |

| /əpːəlɨn/ | to boast |

| /ləpːu/ | boy |

| /qaqːənɨn/ | to protect |

| /fəlːad/ | tired |

| /məlːəg/ | thin |

| /kʼopː/ | box |

| /ʃːad/ | flour |

Gemination also occurs at morpheme boundaries in several cases. When the plural suffix [tə] is added to nouns that end in a sonorant (nasals, liquids, and glides) and involve vowel change in pluralization, the suffix appears as [t:ə]. Additionally, some preverbs cause initial consonants in verb stems to geminate (Abaev 1964; Erschler 2018).

| Singular | Plural |

| χəzar 'house' |

χəzərtːə 'houses' |

| niʃan 'label' |

niʃəntːə 'labels' |

| əʁdaw 'tradition' | əʁdəwtːə 'traditions' |

| nom 'name' | nəmtːə 'names' |

Syllable Structure

Onset clusters in Iron may contain no more than two consonants. Of these two consonants, either a coronal fricative (i.e. [ʃ ʒ] and rarely [s]) must occur in the first position or [w] must occur in second position. Examples of initial consonant clusters are given below. Word final clusters are not as restrictive but also generally contain two consonants (although words with three-consonant final clusters do exist).

|

Coronal Fricative in Position 1 |

[w] in Position 2 |

|

ʃtavd 'thick' |

bwar 'skin' |

|

ʃkʷɨ 'hindquarters' |

nwaʒɨn 'to drink' |

|

ʃqiʃ 'splinter' |

zwap 'answer' |

|

ʃmudɨn 'to sniff' |

swan 'hunt' |

|

ʒnag 'enemy' |

|

|

ʒməlɨn 'to move' |

|

|

ʒʁorɨn 'to run' |

Stress

Stress in Iron Ossetian falls within a two syllable window at the left edge of the prosodic word. Previous work has determined that stress placement in Iron is largely dependent on the vowel in the nucleus of the first two syllables (Abaev 1964; Hayes 1995; Kim 2003; Kager 2012; Erschler 2018). When the first syllable contains a weak vowel /ɨ ə/, stress falls on the second syllable. If the first syllable contains a strong vowel /i e a u o/, stress falls on the first syllable. By all accounts, codas play no role in stress assignment. Examples of this pattern are shown below.

|

Strong Vowel |

Weak Vowel |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ˈχar.bɨʒ | 'watermelon' | əm.ˈbal | 'friend' |

| ˈt͡ʃi.nɨg | 'book' | kər.ˈdo | 'pear' |

| ˈgo.gɨʒ | 'turkey' | wɨ.ˈdon | 'they' |

| ˈdu.sɨn | 'to milk' | pɨ.ˈrɨnz | 'rice' |

| ˈne.ʃi | 'melon' | gə.ˈdɨ | 'cat' |

There is a quite a few exceptions to the above rule, especially among proper nouns. For instance, in the word /irɨʃton/ 'Ossetia', the stress is on the second syllable even though the vowel of the first syllable is a strong vowel (see Dzakhova 2010 for more examples and discussion). Recent work presented by Lubera & Smith (2021) argues that Iron features on onset sensitive system that interacts with the vowel quality pattern shown above. Notably, they argue that complex onsets in Iron are heavier than simplex onsets and that stress is assigned with this weight in mind. When complex onsets occur word initially, the first syllable is stressed regardless of the quality of the vowel. Examples of this are given below.

| ˈʒdə.xɨn | 'to return' |

| ˈʒmən.tɨn | 'to agitate' |

| ˈʃk'ə.rɨn | 'to drive' |

| ˈʃqɨ.wɨn | 'to fly out / pop off' |

| ˈʃt’əl.fɨ.tə | 'dots' |

| ˈʒgə.tə | 'rusts' |

Finally, it must be noted that the domain for stress assignment is often larger than the morphological word (Abaev 1964). For instance, when possessive clitics such as /mə/ 'my' precede a noun, it is counted as part of the word for stress assignment purposes. Therefore, the stress falls on the first syllable of the noun even if the first vowel of the noun is a short vowel. This also occurs on complex predicates. The light verb /kəˈnɨn/ 'to do, to make' receives stress on the second syllable as expected. However, when nonverbal elements are included, they behave as part of the same stress assignment domain. If the non-verbal element contains a strong vowel (e.g. /ˈtaʁd kə.nɨn/) the nonverbal element is stressed. If the nonverbal element contains a weak vowel, the first syllable of the light verb is stressed (e.g. /wəj ˈkə.nɨn/).

| /kə.ˈnɨn/ | 'to do, to make' |

| wəj kənɨn | 'to sell' (lit. to do sale) |

| lɨg kənɨn | 'to cut' (lit. to do cut) |

| taʁd kənɨn | 'to rush' (lit. to do quick) |

Ossetian has lost grammatical gender distinction, but has a rich case system which is in part inherited from Old Iranian. There are nine cases in Ossetian (nominative, genitive, dative, allative, ablative, incessive, adessive, equative, and comitative). Case morphology is agglutinative for the most part. As a result, the nine-case system is not particularly complex in terms of its morphological character.

Case

The nine Ossetian cases are described below:

1- Nominative: The nominative case does not have a marker in the singular (in the plural, we may view the /ə/ in the nominative form of the pluralizing suffix /tə/ as a nominative marker). It must be noted that the use of the Ossetian “nominative” case is wider than the general use of the term “nominative” in most languages. It is used for subjects, direct objects (when the direct object is indefinite or impersonal), vocative constructions, time adverbs (in some cases), etc. Both the morphology and the semantics of the nominative case suggest that it is the default case in Ossetian.

2- Genitive: The suffix /ɨ/ (ы) marks the genitive case. The genitive case is used primarily for marking possessive constructions and some of the other constructions that can be thought of as an answer to the question “of what”. In addition, some direct objects (when they are definite and personal) get the genitive case.

3- Dative: It is marked with the suffix /ən/ (æн), and is used primarily in constructions that can be thought of as an answer to the question “to what”. It is also used for other purposes including indication of goal or purpose.

4- Allative: It is marked with the suffix /mə/ (мæ) for the singular. It answers to the question “to what”, usually indicating direction.

5- Ablative: It is marked by the suffix /əj/ (æй) following consonants and /jə/ (йæ) following vowels. It typically answer to the question “from what”.

6- Incessive: Marked with the suffix /ɨ/ (ы), this case typically answers to the questions “in what” and “where”. Only the third person personal pronouns have independent incessive forms.

7- Adessive: The adessive case is marked by the suffixe /ɨl/. It typically answers to the questions “on what” and “about what”.

8- Equative: It is marked by the suffix /aw/ (ау) and typically answers to the questions “how” and “like what”.

9- Comitative: It is marked by the suffix /imə/ (имæ) and answers to the question “with what”.

Personal Pronouns

In the first person personal pronouns, the nominative (/əz/) and dative (/mən/) forms are cognates of the typical first person pronouns in other Iranian languages with case distinction. In most other cases, the morphology of case marking is agglutinative; the case-marking suffix appears as a suffix attached to a main morpheme. The genitive form serves as the base for these agglutinative suffixes. The Ossetian personal pronouns are shown in the table below.

| Nominative | Genitive | Dative | Allative | Ablative | Incessive | Adessive | Equative | Comitative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | /əz/ | /mən/ | /mənən/ | /mənmə/ | /mənəj/ | — | /mənɨl/ | /mənaw/ | /memə/ (fr. /mənemə/) |

| you (sg.) | /dɨ/ | /dəw/ | /dæwən/ | /dæwmə/ | /dæwəj/ | — | /dəwɨl/ | /dəwaw/ | /dəmə/ (fr. /dəwemə/) |

| he/she/it | /wɨj/ | /wɨj/ | /wɨmən/ | /wɨmə/ | /wɨməj/ | /wɨm/ | /wuɨl/ | /wɨjaw/ | /wɨimə/ |

| we | /maχ/ | /maχ/ | /maχən/ | /maχmə/ | /maχəj/ | — | /maχɨl/ | /maχaw/ | /maχimə/ |

| you (pl.) | /sɨmaχ/ | /sɨmaχ/ | /sɨmaχən/ | /sɨmaχmə/ | /sɨmaχəj/ | — | /sɨmaχɨl/ | /sɨmaχaw/ | /sɨmaχimə/ |

| they | /wɨdon/ | /wɨdon/ | /wɨdonən/ | /wɨdonmə/ | /wɨdonəj/ | /wɨdonɨ/ | /wɨdonɨl/ | /wɨdonaw/ | /wɨdonimə/ |

Ossetian also has a set of enclitic personal pronouns. The nominative case does not have enclitic forms. Note that possession can be marked using the genitive form of either the full pronouns or the enclitic pronouns.

Verbs

As is typical of Iranian languages, each Ossetian verb has a past stem and a present stem. Past stems generally end with a /t/ (т) or /d/ (д). In the simplest cases, the past stem is formed by adding a /t/ (Or a /d/, if the preceding sound is not a voiceless consonant or a /z/) to the end of the present stem. A few examples are shown in the table below.

| Present stem | Past stem | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| mar (мар) | mard (мард) | to kill |

| dar (дар) | dard (дард) | to hold, to keep |

| war (уар) | ward (уард) | to rain |

| kʼaχ (къах) | kʼaχt (къахт) | to dig |

| dəs (дæс) | dəst (дæст) | to shave |

| wɨn (уын) | wɨnd (уынд) | to see |

| dom (дoм) | domd (дoмд) | to demand |

The formation of verbs from the stems is also similar to most other Iranian languages. Verbs are conjugated for the six person-number combinations by changing the personal suffix, which agrees with the subject in both present and the past (no ergativity). The paradigm is shown in the example below for the verb “to pour”, /kalɨn/ (калын).

| English | Ossetian |

|---|---|

| I pour. | kalɨn. (калын) |

| You (sg.) pour. | kalɨs. (калыс) |

| She/He/It pours. | kalɨ. (калы) |

| We pour. | kaləm. (калæм) |

| You (pl.) pour. | kalut. (калут) |

| They pour. | kalɨnt͡s. (калынц) |

In the past tense, transitive and intransitive verbs are conjugated differently. The table below shows the conjugation for the transitive version of “to pour” in the past tense.

| English | Ossetian |

|---|---|

| I poured. | kaldton. (калдтон) |

| You (sg.) poured. | kaldtəj. (калдтæй) |

| She/He/It poured. | kaldta. (калдта) |

| We poured. | kaldtam. (калдтам) |

| You (pl.) poured. | kaldtat. (калдтат) |

| They poured. | kaldtoj. (калдтoй) |

The intransitive conjugation of the same verb (“to pour”) for the past tense is shown below:

| English | Ossetian |

|---|---|

| I poured. | kaldtən. (калдтæн) |

| You (sg.) poured. | kaldtə. (калдтæ) |

| She/He/It poured. | kald(is). (калдис) |

| We poured. | kaldɨstəm. (калдыстæм) |

| You (pl.) poured. | kaldɨstut. (калдыстут) |

| They poured. | kaldɨstɨ. (калдысты) |

Sample Text

The following sample text and most of the commentary are taken from Oranskij (1963).

| æртæ | барæдж-ы | фæдæргæвст | æркæн-ынц=йæ | фæндаг. |

| ərtə | barəd͡ʒ-ɨ | fədərgəvst | ərkən-ɨnt͡s=jə | fəndag. |

| three | rider-GEN | intersection | cut.PRS-3PL.PRS=3SG.GEN | way. |

“Three riders block his/her way.” (lit. “Three riders cross his/her way”)

ərtə: “three”. From Old Iranian “θraya”, related to Old Persian “θri”, Greek “treīs”, and Latin “ters”.

barəd͡ʒ-ɨ: from /barəɡ/ “rider” + the genitive case marker. Compare /barəg/ with Old Persian “asa-bāra” (lit. “taken with horse”) and Modern Persian “savār”. The noun follows the number “three” and has to take the genitive case. The final consonant /ɡ/ of /barəg/ changes to /d͡ʒ/ before the vowel /ɨ/.

fədərgævst: “intersection”. From /fəd/ “following, after” (cf. Modern Persian “pey”, Latin “peda”) and /ərgəvst/ past participle of /ərgəvdɨn/ “to cut”.

ərkən-ɨnt͡s: “they cut (present)”. Infinitive: /ərkənɨn/. The combination /fədərgəvst ərkənɨn/ is a complex predicate meaning “to cross”, “to come from a different direction and block someone’s way”.

jə: The enclitic genitive third person singular pronoun used in a possessive construction (“his way”).

fəndəg: “way”, “path”. Related to Modern Persian “pand” (“advice”; undergone semantic shift from “path” to “right path” to “advice”).

Bibliography

Abaev, Vasiliĭ Ivanovich (1964). "A grammatical sketch of Ossetic." Translated by Steven P. Hill. In International Journal of American Linguistics 30(4).

Dzakhova, B. T. (2010). "Ob osetinskom udarenii [On Ossetian accents]". Вестник РГГУ. Серия: Литературоведение. Языкознание. Культурология, 9 (52), 9-26.

Erschler, David (2018). "Ossetic." In Geoffrey Haig & Geoffrey Khan (eds.), The languages and linguistics

of Western Asia, De Gruyter Mouton. 861–891.

Hayes, Bruce (1995). Metrical Stress Theory: Principles and Case Studies. Universty of Chicago

Press.

Hettich, Bela (2002). Ossetian: Revisiting inflectional morphology. University of North Dakota dissertation.

Isaev, M. I. (1959). "Ocherk fonetiki osetinskogo literaturnogo yazyka [Essay on the phonetics of the Ossetian literary language]". Severo-osetinskoe knizhnoe izdatelʼstvo Ordzhonikidze.

Kager, René (2012). "Stress in windows: Language typology and factorial typology." Lingua 122(13). 1454–1493.

Kim, Ronald (2003). "On the historical phonology of Ossetic: The origin of the oblique case suffix". Journal

of the American Oriental Society 123(1). 43–72.

Smith, Ryan and Lubera, Amber (2021). "Onset-sensitive stress in Iron Ossetian." Presented at the 18th Old World Conference on Phonology.

Oranskij, Iosif Mikhailovich (2007). “Zabānhā-ye irani [Iranian languages]”. Translated by Ali Ashraf Sadeghi. Sokhan publication.

Thordarson, Fridrik (1989). “Ossetic.” Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum, Wiesbaden: 456-479.

Thordarson, Fridrik (2009). “OSSETIC LANGUAGE i. History and description” Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition, available at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/ossetic